When reading news stories and before sharing them, it is vital to stop for a minute and evaluate the source. We all know that “fake news” and disinformation is rife and it is easy to get caught out by a convincing and emotive headline or story. The first thing to do is to consider your own bias as well as your emotional response to a specific story or article. As well as this, sharing articles based containing misinformation encourages it to spread, the best action to take when you see something that is not factually correct or proven, is nothing. The following definitions will help you to understand and recognise factors that can affect our ability to critically evaluate information.

Definitions

Confirmation bias

Confirmation bias refers to processing information by looking for, or interpreting, information that is consistent with one’s existing beliefs. This biased approach to decision making is largely unintentional and often results in ignoring inconsistent information. Existing beliefs can include one’s expectations in a given situation and predictions about a particular outcome. People are especially likely to process information to support their own beliefs when the issue is highly important or self-relevant.

Cognitive bias

… refers to a pattern of selectively processing emotional information in one’s environment.

Cognitive bias can make us very vulnerable to fake news in the following areas - (1) attention, (2) interpretation, and (3) memory. If we are anxious about something or an issue, we can focus our attention on one issue such as climate change and interpret everything through that issue only remembering negative stories. We ignore other more balanced, nuanced and positive stories. This can make us very vulnerable to fake news stories that focus on an issue we are worried about.

Echo chamber

… an environment, especially on a social media site, in which any statement of opinion is likely to be greeted with approval because it will only be read or heard by people who hold similar views

Filter bubble

… a unique universe of information for each of us … which fundamentally alters the way we encounter ideas and information.

Eli Pariser invented the term ‘filter bubble’.

In December 2009, Google began customising its search results for all users so that news content etc. becomes personalised based on the collection of your search history and data analysis. This means that as users the way we consume information and news has changed. News in the outside world is being filtered so that we only see news that reflects our worldview.

So, how do we evaluate information sources? The CRAAP test is a list of questions designed to help you to analyse the validity and reliability of a source based on the criteria below and is used in schools and universities all over the world.

- Currency

- Relevance

- Authority

- Accuracy

- Purpose

There are many other similar rubrics you can use. IF I APPLY is one developed by librarians in the US and focuses on examining our own thoughts, feelings and personal biases towards particular topics. It is argued that this can severely damage our ability to research effectively and only when we confront this can we fully engage with the process of critically evaluating information.

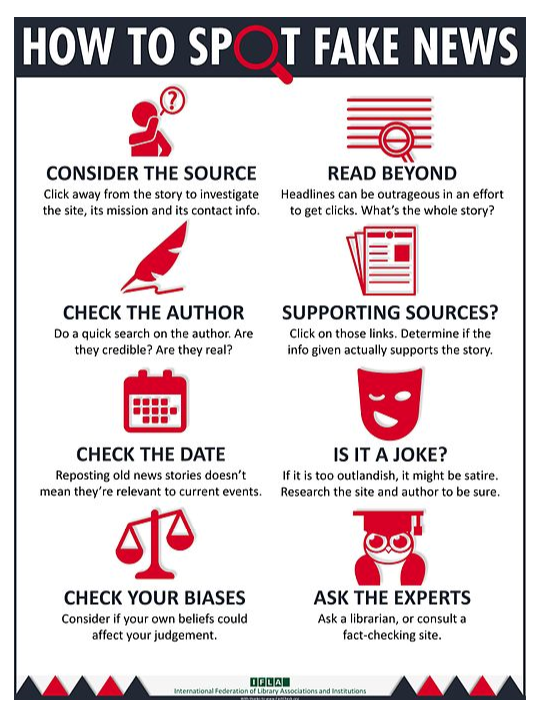

The International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions (IFLA) have produced the following infographic with eight simple steps (based on FactCheck.org’s 2016 article How to spot fake news to determine

the verifiability of a news site  Infographic available to download here

Infographic available to download here

Attribution: IFLA [CC BY 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licences/by/4.0)]

The following quick checklist will help you analyse news sources. Some have been adapted from tips by Melissa Zimdars

General tips for analysing news sources:

- Use the Mediabias/factcheck website if you are unsure about the reliability of a news outlet or website. You can check the political bias and credibility. This is a great resource providing detailed reports and analysis including the history, ownership and in some cases who the website/news outlet is funded by.

- Watch out if reputable news sites are not also reporting a story. Sometimes lack of coverage is the result of corporate media bias and other factors, but there should typically be more than one source reporting on a topic or event.

- Is there an identifiable author? Lack of author attribution may signify that the news story is suspect and requires verification.

- Some news organisations let bloggers post under the banner of particular news brands; however, many of these posts do not go through the same editorial process.

- Odd domain names generally indicate equally odd and rarely truthful news.

- Look at the domain extension as this detail can give some indication of reliability. Avoid websites that end in “.lo” as these sites take pieces of accurate information and then package that information with other false or misleading “facts” (sometimes for the purposes of satire or comedy).

- Watch out for common news websites that end in “.com.co” as they are often fake versions of real news sources (remember: this is also the domain for Colombia) e.g. washingtonpost.com.co is not the same as https://www.washingtonpost.com (official site)

- Bad web design can also be a sign that what you are looking at should be verified or read in conjunction with other sources.

- Check the “About Us” tab on websites or look up the website on Snopes or online for more information about the source.

- If the story makes you angry it’s probably a good idea to keep reading about the topic via other sources to make sure the story you read wasn’t purposefully trying to make you angry (with potentially misleading or false information) in order to generate shares and ad revenue.

- If the website you are reading encourages you to share the private personal information of another person or reveal the identity of an online poster without their consent, i.e. doxing, it is unlikely to be a legitimate source of news.

- It is always best to read multiple sources of information to get a variety of viewpoints and media frames.

- Remember to check your own biases and read outside your filter bubbles

Fact checking websites

Fact checks alone are not enough to halt the spread of misinformation. Full Fact work with government departments and research institutions to improve the quality and communication of information at source. They also provide a fact-checking toolkit to give people the tools they need to make up their own minds.

Hoaxy visualizes the spread of claims and related fact checking online. A claim may be a fake news article, hoax, rumour, conspiracy theory, satire, or even an accurate report. Anyone can use Hoaxy to explore how claims spread across social media. You can select any matching fact checking articles to observe how those spread as well.

Launched in 2004, Media Matters for America is a web-based, not-for-profit, progressive research and information centre dedicated to comprehensively monitoring, analysing, and correcting conservative misinformation in the U.S. media.

Compiled by women and focussing on women, this site compiles a daily recap of the most important news from Europe and a weekend review of the most relevant stories. There is a recent focus on debunking fake news stories.

One of the oldest fact-checkers out there, with many excellent features. Their mission statement states that: “fact-checking journalism is the heart of PolitiFact. Our core principles are independence, transparency, fairness, thorough reporting and clear writing.”

FactCheck.org’s SciCheck feature focuses exclusively on false and misleading scientific claims that are made by partisans to influence public policy.

Attempts to give accurate information about rumours, misinformation, folklore, myths and urban legends on a variety of topics, including war, business, events, toxins, science, military, popular culture.

A site dedicating to fact checking in Africa.

You can install the NewsGuard plugin in either your Google Chrome, Microsoft Edge, Mozilla Firefox, or Apple Safari browser with one click. As you browse the news, you will see the NewsGuard icon next to news links on search engines and social media feeds, such as Google, Bing, Facebook and Twitter. Green rated sites follow basic standards of accuracy and accountability. Red rated sites do not. Blue rated sites refer to platforms, orange rated sites indicate satire sites, and grey rated sites are those we are in the process of rating and reviewing. Hover your mouse over the NewsGuard icon for a brief description of each site and why it received its rating. Click “See the full Nutrition Label” to read a longer description of the site and how it rates on each of our nine criteria.

References

Casad, B. J. (2007) ‘Confirmation Bias.’ InBaumeister, R. F. and Vohs, K. D. (eds.)Encyclopedia of social psychology. Los Angeles: Sage, pp. 163-164.

Collins English Dictionary. (No date) echo chamber, n. 2. No place of publication: Collins. [Online] [Accessed on 26th July 2018] https://www.collinsdictionary.com/dictionary/english/echo-chamber

International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions. (2019) How to spot fake news.[Online] [Accessed on 30thOctober 2019 https://www.ifla.org/publications/node/11174

Kiely, E. and Robertson, L. (2016) How to spot fake news.Factcheck.org. [Online] [Accessed on 30th October 2019] https://www.factcheck.org/2016/11/how-to-spot-fake-news/

Kuckertz, J. M. and Amir, N. (2017) ‘Cognitive Bias.’InWenzel, A. (ed.)The SAGE encyclopedia of abnormal and clinical psychology. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage, pp. 748-749.

London South Bank University. (2019) Fake news.[Online] [Accessed on 30thOctober 2019] https://libguides.lsbu.ac.uk/fakenews/home

Manchester Metropolitan University. (2019) Evaluating sources of information. [Online] [Accessed on 30thOctober 2019] https://libguides.mmu.ac.uk/evaluatingsources

Meriam Library. (2010) Evaluating information – applying the CRAAP test. California: California State University. [Online] [Accessed on 31stOctober 2019] https://library.csuchico.edu/sites/default/files/craap-test.pdf

Pariser, E. (2011) The filter bubble: what the Internet is hiding from you.New York: Penguin, p. 9.

Penn State University Libraries. (2019) IF I APPLY. [Online] [Accessed on 31stOctober 2019] https://guides.libraries.psu.edu/WC/HPA210

Zimdars, M. (2016) False, misleading, clickbait –y, and satirical “news” sources.[Online] [Accessed on 30thOctober 2019] https://docs.google.com/document/d/10eA5-mCZLSS4MQY5QGb5ewC3VAL6pLkT53V_81ZyitM/preview